the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Concurrent aerodynamic design of the wing and the turbines of airborne wind energy systems

Filippo Trevisi

Gianni Cassoni

Mac Gaunaa

Lorenzo Mario Fagiano

The aerodynamic design of the fly-gen airborne wind energy system aircraft, referred to as a windplane here, is a largely unexplored yet crucial problem for improving power production. To this end, an engineering model for the aerodynamics of the onboard turbines, the aerodynamics of the wing, and their interactional aerodynamics is developed and coupled to a steady-state windplane model and a far-wake model. This novel comprehensive model is then used to design the windplane aerodynamics for a given wingspan. Initially, a design space exploration study reveals that placing the turbines at the wing tips and rotating them inboard down increases the power production compared to other locations and rotation directions. This improvement arises because the turbines' wake swirl reduces the wing's induced drag, which increases flight speed and, consequently, the generated power. Moreover, airfoils with a high lift-to-drag ratio are found to be optimal for windplanes. As a consequence, NACA4421 airfoils are used for the design of the wing and the tip-mounted turbines. The trapezoidal wing with constant twist which maximizes power production has an aspect ratio of 5.1 and a taper ratio of 0.60. By design, the onboard turbines operate at a low tip speed ratio of 1.9 to increase the wake swirl. The results from the vortex models of the wing, the turbines, and their interaction show very good agreement with the lifting line, the vortex lattice method, and the vortex particle method implemented in the well-established code DUST. Finally, the windplane is studied with DUST at different wing angles of attack and at different turbine tip speed ratios to characterize its behavior away from the design point. The maximum in power production is observed near to the design point, well separated from the stall regions of both the wing and the turbines.

- Article

(13824 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Airborne wind energy systems (AWESs) harvest wind power by means of a fully autonomous aircraft connected to the ground by a tether. AWESs can be classified as crosswind, tether aligned, or rotational (Vermillion et al., 2021). Most industrial and research activities focus on crosswind AWESs, whose working principles were first described by Loyd (1980). Crosswind AWESs move in a fast motion roughly perpendicular to the wind direction and generate power either with onboard small wind turbines (fly-gen AWESs), as studied in this paper, or by pulling the tether and unwinding a generator on the ground (pumping AWESs). For more details, Fagiano et al. (2022) give an overview of the state of the art of these systems.

Fly-gen AWESs fly figure-of-eight or circular trajectories and generate power with the onboard turbines. The electrical power is transmitted to the ground via the tether, which has both a structural and an electrical component. The aircraft of fly-gen AWESs is termed to be a windplane in this paper. It is a rather unique system, whose design is far from being fully understood. This is due to the need to operate in very different phases (take-off and landing, power production, transitions) and at a broad range of wind speeds and to maximize the converted power while meeting structural and controllability requirements. Currently, fly-gen systems are actively developed by companies such as Kitekraft GmbH (2025) and WindLift (2025) and were developed by Makani Technologies LLC (2025), which ceased operations in 2020.

KiteKraft's design is based on a box wing, with turbines that are distributed along the span of both wings. The AWES flies figure-of-eight trajectories and operates the windplane at very high lift coefficients (CL≈4.5), achieved through multi-element airfoils (Bauer et al., 2018). The onboard turbines are designed for the power generation and to sustain the AWES during hover but not in conjunction with the wing design (Frirdich, 2019). The WindLift design is not disclosed, and only a limited amount of information is publicly available. Their design is characterized by a single wing with four turbines mounted on pylons. On the other hand, the Makani's development is well documented in publicly available sources. After the shut-down, Makani engineers released two reports summarizing the design, analyses, and testing methodologies (Echeverri et al., 2020a, and Echeverri et al., 2020b). Makani's last prototype, the M600, had a wingspan of 26 m, an aspect ratio of 20, and eight turbines mounted on pylons along the wing. Before the shut-down, Makani engineers re-designed the AWES to overcome major shortcomings, resulting in the MX2 design. The MX2 was designed to feature a wingspan of 26 m, an aspect ratio of 12.5, and eight turbines. The wings' and turbines' designs were carried out separately. The turbines are designed to generate power and to provide the thrust to sustain the AWES during hover. Their wing is designed to maximize the power-harvesting factor1, as explained by Tucker (2020) and in an earlier paper by Vander Lind (2013). The power-harvesting factor is defined by Diehl (2013) as the ratio between the generated power and the kinetic energy flux (or wind power density) passing through the wing planform area. This definition is purely a normalization choice since no actual flow passes through the planform area, which is, however, used as a reference area for normalization. Wings designed to maximize the power-harvesting factor have a high aspect ratio (Echeverri et al., 2020a; Bauer et al., 2018; Fasel et al., 2017; Trevisi et al., 2021, among others) and use unconventional airfoils, which are designed to maximize the metric (Bauer et al., 2018; De Fezza and Barber, 2022; Porta Ko et al., 2023; Rangriz and Kheiri, 2025, among others).

Recently, Trevisi (2024) introduced a new design methodology for windplanes, performing the aerodynamic design per a given wingspan. This is achieved by maximizing a new power coefficient2, defined as the ratio between the generated power and the kinetic energy flux (or wind power density) passing through a disk with a radius equal to the wingspan (Trevisi et al., 2023a). This reference area does not correspond to an actual flow cross-section but is just used as a reference area to normalize the generated power. Wings designed to maximize this power coefficient have low aspect ratios (approximately between 4 and 7) and use conventional efficient airfoils (i.e., airfoils with high ). This new methodology is improved in this paper to concurrently design the main wing and the onboard turbines. Three turbine positions are considered: in front of the wing's leading edge at half the semi-wing span, at the wing tips, and above or below the wing. If they are placed above or below, they need pylons, which have an associated aerodynamic drag and decrease the system performances. If they are placed in front of the wing, they reduce the apparent wind speed experienced by the involved wing aerodynamic sections, which reduces lift force. Conversely, airplanes with propellers in front of the wing achieve an increase in aerodynamic lift. Another relevant aerodynamic effect is the swirl in the turbine wake. Airplane designers have long exploited this effect by placing the onboard propellers at the wing tips (Snyder and Zumwalt, 1969; Patterson and Bartlett, 1985), allowing the downstream aerodynamic sections to experience a beneficial change in inflow angle, leading to a decrease in induced drag. Miranda and Brennan (1986) started the theoretical and numerical investigation of the decrease in induced drag due to tip propellers and tip turbines. They developed a vortex model similar to the one presented in this paper to assess the benefit of placing the rotors at the wing tips. Recently, Sinnige et al. (2019b) performed wind tunnel tests comparing tip propeller configurations to conventional layouts and studied their performance under energy-harvesting conditions (Sinnige et al., 2019a). Taking inspiration from this aeronautical experience, here, we design the windplane onboard turbines with engineering models. We design the rotors for the generation phase only and do not consider whether they generate enough thrust in the hover state. This is done to focus on the ideal aerodynamic design of the windplane to fulfill its main functionality, i.e., power generation. The design can be modified later to cope with the take-off and landing phases, which are less demanding in terms of power ratings (Fagiano and Schnez, 2017). We validate the proposed framework with the lifting line, the vortex lattice method, and the vortex particle method implemented in DUST (Tugnoli et al., 2021). This code is open-source and has been validated for wing propeller studies (Niro et al., 2024). Finally, we use DUST to characterize the wing and rotor design away from the design point. The vortex particle method has recently been used by Mehr et al. (2024) to analyze the Makani prototype (characterized by rotors mounted on pylons) and to investigate the effects of rotor rotation direction and vertical and streamwise rotor position on the overall aerodynamic performance without however moving the rotors in front of the wing and along the wing span.

This paper is organized as follows: in Sect. 2, the aerodynamic modeling framework is introduced; in Sect. 3, the aerodynamic optimization problem formulation is introduced, and a design space exploration study on the turbine positions and on the optimal airfoil characteristics is carried out; in Sect. 4, the vortex particle code DUST, used for validation and analysis, is introduced; in Sect. 5, the optimal design problem is solved, the solution is compared with DUST, and the design is studied away from the design point; in Sect. 6, the main conclusions are discussed, and future work is suggested. A list of symbols is given at the end of the paper.

We start by formulating the modeling framework for the optimal design problem of the wing and the rotors. The model is meant to be as simple as possible while still capturing the relevant physical phenomena.

2.1 Windplane steady-state model

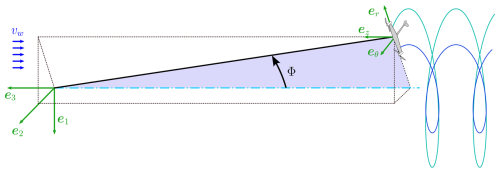

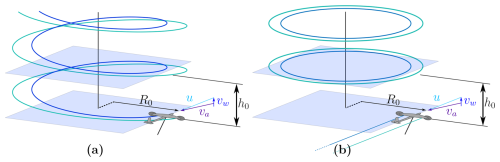

We assume a steady-state equilibrium, neglecting gravity and assuming a circular fully crosswind trajectory with steady uniform wind. Indeed, Trevisi (2024) shows that the aerodynamic problem is not influenced by the dynamic problem. Referring to Fig. 1, the force balance is written in the cylindrical coordinate system , where eθ points tangentially, er points radially, and ez points axially.

Figure 1Ground coordinate system and cylindrical coordinate system . vw is the incoming wind speed, and Φ is the opening angle of the circular trajectory, centered on the light-blue dash-dotted line. The light- and dark-blue helices represent the right- and left-trailed vortices.

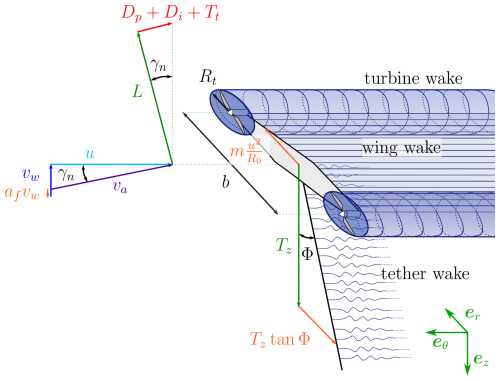

The aerodynamic forces and the main wake components are shown in Fig. 2. Considering the velocity triangle and the inflow angle in the near wake γn, the force balances in the three axes are

where L is the aerodynamic lift, Dp is the parasite drag, Di is the induced drag, Tt is the turbine thrust, m is the system mass (equal to the aircraft mass plus one-third of the tether mass, as derived from Trevisi et al., 2020), u is the tangential velocity, R0 is the trajectory radius, Tz is the axial component of the tether force, and Φ is the opening angle of the circular trajectory.

Figure 2Velocity triangle, forces acting on the windplane in crosswind steady-state and main wake components.

The aerodynamic lift L, defined to be perpendicular to the apparent velocity va, is

where ρ is the air density, CL is the wing lift coefficient, and the wing area A is

where b is the wing span, and AR is the wing aspect ratio.

The aerodynamic parasite drag is

where CD,p is the parasite drag coefficient, defined as

CD,a is the three-dimensional coefficient due to the airfoils, and CD,te is the equivalent tether drag (Trevisi et al., 2020):

where Cd,te is the tether section drag coefficient, Lte is the tether length, and Dte is the tether diameter.

The induced drag is

where CD,i is the induced drag coefficient of the near wake. Indeed, Trevisi et al. (2023b) show that the induced velocities due to the near wake (first half rotation of the helicoidal wake shown in Fig. 1) can be taken into account with an induced drag coefficient computed assuming the trailed vortex filaments as straight, as done in this work. More details about this modeling approach are given in Sect. 2.4.

The thrust force produced by the onboard wind turbines is

where CT,t is the thrust coefficient of the onboard wind turbines, and At is the total rotor area. We define the onboard wind turbine radius as a function of the wing semi-span as

where the total rotor area At, assuming two turbines nt=2, is

In this work, we assume two turbines to simplify the problem as much as possible. However, the modeling framework is general, and different configurations might be investigated.

The employed model to estimate the thrust coefficient CT,t of the onboard turbines is described in Sect. 2.2, while the models for the aerodynamic coefficients CD,a and CD,i are detailed in Sect. 2.3.

The force balance along the tangential direction (first component in Eq. 1) can be written as

where E is the windplane aerodynamic efficiency, including the thrust of the turbines.

The inflow angle in the near wake, γn, can be found by considering the tangential velocity to the plane's path u and by subtracting the induced velocity due to the far wake afvw from the free wind velocity vw (Trevisi et al., 2023b):

where is the wing speed ratio.

The wing speed ratio λ can be found by equating Eqs. (11) and (12) and using the definition of the aerodynamic forces:

The power equation can be written with respect to the onboard turbines as

where CP,t is the power coefficient of the onboard wind turbines, and large values of λ are assumed (λ2≫1). In practice, the wing speed ratio ranges from λ≈5 to λ≈10, thus justifying this assumption.

The windplane power coefficient, using as a reference area the disk with the radius of the wingspan (Trevisi et al., 2023a), is

The windplane thrust coefficient, similar to the conventional turbines' thrust coefficient, is defined to inform us about the aerodynamic force which does work to the wind (i.e., the component of the aerodynamic force which is parallel to the wind direction and thus slows it down) as follows:

where small inflow angles in the near wake, i.e., γn≪1, are assumed, such that the axial component of the tether force can be approximated with the lift force Tz≈L (third component in Eq. 1). Writing the turning radius as R0=Ltesin Φ, the radial equilibrium (second component in Eq. 1) can be formulated to find the opening angle Φ such that the wingspan is fully crosswind (i.e., the lift is not used for turning):

2.2 Onboard-turbine model

In order to evaluate the onboard turbines' performance and the effect of their wakes on the wing, we use the vortex cylinder model introduced by Branlard and Gaunaa (2016), which accounts for the radially varying circulation by superposing the vortex cylinder models developed by Branlard and Gaunaa (2015). The model is an actuator disk model like the momentum-based framework that blade element momentum (BEM) models are based on. The added value provided by the vortex cylinder model is that it includes the effect of the pressure drop due to wake rotation that is neglected in the momentum-based models. The importance of this effect increases as the tip speed ratio is decreased, which is when the wake rotation increases.

Let us define the parameter k as , where Γt(rt) is the bound circulation of the annulus, Ωt is the rotor angular velocity, u is the inflow velocity into the rotor, and is the radial coordinate. Then, the rotor quantities can be evaluated for a given radial distribution of the parameter k(rt) and a given tip speed ratio . The tangential induction at the turbine radius rq can be evaluated for a given value of kq(rq) as

where the local speed ratio is . The dimensional tangential velocity (swirl) at the rotor disk can then be evaluated as

The local thrust coefficient is defined as

such that the rotor thrust coefficient is

The effect of the rotation of the wake is a decrease in the pressure toward the rotational axis. The part of the local thrust coefficient corresponding to this is the rotational thrust coefficient, which is

The induction at each radial station is

such that the reduction in axial velocity at the rotor disk is

The local power coefficient is

and the rotor power coefficient is

This model enables the estimation of the turbine thrust coefficient CT,t (Eq. 21) and the power coefficient CP,t (Eq. 26) for a given distribution of the parameter k(rt) and tip speed ratio λt. Moreover, it provides the velocities induced in the turbine wake3, which are twice the velocities in the rotor disk. Veldhuis (2004) highlights that a swirl recovery factor of should be included to properly model the rotor-wing interaction, when the velocities in the rotor wake are considered to be inputs into the wing. The reduction in the slipstream induction and swirl can be attributed to the wing-induced upwash. The correct induced velocities to be used as inputs for the wing are then the induced velocities in the rotor disk. This is explained by Miranda and Brennan (1986) as a generalization of Munk stagger theorem (Prandtl, 1924), which is used to compute the induced drag of multiple wings (e.g., main wing and horizontal stabilizer). This theorem states that the total induced drag of systems of multiple wings with a fixed Trefftz-projected bound circulation is independent of the streamwise location of each of the wings. This shows that the total induced drag of a multiple-wing system can be calculated by moving the wings to the same streamwise position. Similarly, the correct induced drag of the rotor–wing system in the present case is calculated by moving the rotors to the same streamwise position as that of the wing. For this reason, the induced velocities wt and ut (Eqs. 19 and 24), which are the values at the rotor disk (equal to half the values in the turbine far wake), are used as inputs for the wing.

These considerations also point out that placing the turbines after the wing would not change the overall induced drag as long as they are placed in the same stream-wise location. Thus, in this paper, we only study the case in which the rotors are placed in front of the wing.

2.3 Wing model

Here, we introduce the wing model, based on the lifting-line theory of Weissinger (1947). An infinitesimal segment of vortex filament dl, located at l and with vortex strength Γ, induces a velocity dV at an arbitrary point P. Defining the distance from dl to P as r, the induced velocity dV can be evaluated with the Biot–Savat law:

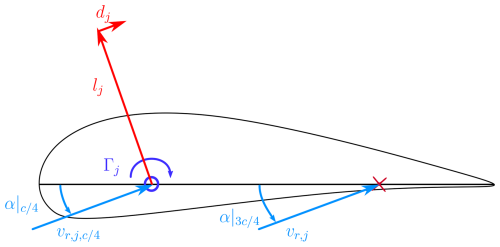

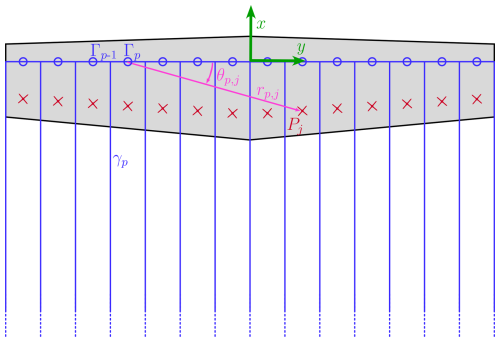

Referring to Fig. 3, we model the wing as a straight lifting line pointing along the y direction, discretized in Np elements, with Np being an even number. The chord direction of the airfoil at the wing center is taken to be equal to the x direction. Each element p is characterized by a bound vortex of strength Γp located along the direction of the quarter-chord line. According to the Helmholtz's vortex theorem, a vortex must extend to the boundaries of the fluid so that each element trails two vortexes of strength equal to Γp from its extremes. The number of trailed vortices is then Np+1, with intensity γp = . According to Pistolesi's theorem, following the implementation by Damiani et al. (2019), we evaluate the induced velocities at the chord-wise position of the three-quarter chord of each element. The distance r of the evaluation point with respect to the reference system placed on the quarter-chord line from a generic point located at is

with the angle θj being

The velocity induced by an infinitesimal portion of the bound vortex located at at the evaluation point Pj can be evaluated with Eq. (27), where and r are given in Eq. (28):

with being obtained by differentiating Eq. (29) with x=0.

The velocity induced by the finite bound vortex p is then

The velocity induced by the trailed vortex p at the evaluation point Pj is evaluated by integrating Eq. (27), where and r are given in Eq. (28):

with being obtained by differentiating Eq. (29) with y=yp.

Figure 3Wing geometry. The bound vorticity Γp of the element p and the vorticity of the trailed vortex p are shown in blue. The red crosses are the evaluation points, with Pj being the evaluation point of element j. The distance rp,j and the angular position θp,j of evaluation point Pj with respect to the start of the vortex filament p are shown in purple.

Since the induced velocities from the three-dimensional vorticity distribution are evaluated at the three-quarter chord point, the induced velocity from the two-dimensional vorticity distribution also needs to be evaluated at the same point (Damiani et al., 2019). The 2D bound vortex induces a velocity at the evaluation point:

The total induced velocity at the evaluation point Pj is then

The relative wind velocity at the three-quarter chord point of the aerodynamic section j takes into account the free-stream velocity va, as well as the velocities induced by the turbines by the turbines vt,j and by trailed vorticity wj:

where α is the undisturbed wing angle of attack, defined as the angle between the chord line of the airfoil at the wing center (x direction) and the undisturbed inflow.

The angle of attack used to compute the airfoil lift Cl and drag coefficients Cd is

where βj is the local twist angle (i.e., the angle between the x direction and the local airfoil chord line), and vr,j(3) and vr,j(1) are the third and first elements of the relative wind velocity (Eq. 35).

The sectional lift lj and drag dj should, however, be projected according to the velocity triangle at the quarter chord lines (Li et al., 2022). The velocity at the quarter-chord line () takes into account the free-stream velocity va, as well as the velocities induced by the turbines vt,j and by trailed vorticity :

The velocity induced by the trailed vorticity is

The angle of attack used to project the lift and drag is then

The nonlinear problem formulated to find the induced velocities at each aerodynamic section – and, thus, the aerodynamic coefficients – is solved iteratively by imposing

at each evaluation point.

The lift force at each aerodynamic section is

and the wing lift coefficient is defined as

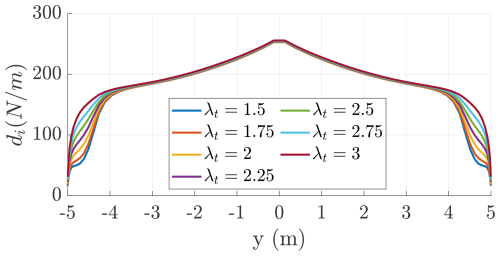

The integral induced drag Di can be computed from the induced drag at each wing section di,j, which corresponds to the local lift lj times the local induced angle of attack . The induced drag coefficient is

Finally, the three-dimensional profile drag coefficient due to the airfoils CD,a can be computed as

where Cd,j is the airfoil drag coefficient.

2.4 Windplane wake model

To conclude the modeling of the windplane aerodynamics, we need to find how much the wind is slowed down, which means finding the induction af in Fig. 2. Trevisi et al. (2023b) show that, for a large turning radius and large wing speed ratios , the aerodynamic induction a generated by the helical vortex system (Fig. 5a) can be modeled as the sum of two terms: one due to the first half rotation of the helical vortex filaments (the near-wake induction an) and one related to the semi-infinite cascade of vortex rings (the far-wake induction af), as in Fig. 5b. The near-wake induction or the near-wake-induced drag Di can be computed by assuming straight semi-infinite trailed vortices, as carried out in Sect. 2.3.

Figure 5Left and right rolled-up trailed helicoidal vortices (a) and relative modeling after assumptions (b) (Trevisi et al., 2023b).

The far-wake induction af can instead be computed by summing up the contribution of each vortex ring. Their strength is equal to the tip vortex strength,

and their spanwise position is

The wake pitch is

where vw(1−ar) is the axial velocity of the vortex rings. Gaunaa et al. (2020) evaluate the axial velocity of the vortex rings by modeling them as infinite straight vortices and assuming that the dominant effect in the motion of the vortices is the vorticity of the nearest vortex. With this model, tested to be valid by Trevisi et al. (2025), the convection velocity of the rings is

The induction due to the far wake af (Fig. 2) can now be evaluated with (Trevisi et al., 2023b)

where is the tip vortex normalized position, and is the normalized torsional parameter of the helicoidal wake. The shape factor Υk(η,λ0) models the induction of one vortex ring and can be computed in closed form as (Trevisi et al., 2023b)

where F(f) and E(f) are the complete elliptic integral of the first and second kind, respectively, and .

In this section, we formulate the aerodynamic design problem formulation, and we explore the optimal design space. The optimal aerodynamic design problem reads as

where the optimization variables x are the induction due to the far wake af; the bound circulation at each wing aerodynamic section Γ; the wing angle of attack α; the chord at the wing center c0, the taper ratio of the trapezoidal wing tr; the onboard turbine tip speed ratio λt; and the parameter Kt, determining the radial distribution of k(rt) (see Sect. 2.2).

The induction due to the far wake af is settled by the optimizer to satisfy (Eq. 49), and the bound circulation at each aerodynamic section Γj is settled to satisfy (Eq. 40).

The objective function is the power coefficient CP (Eq. 15). Optimizing for this power coefficient is equivalent to optimizing for the shaft power while keeping the wing span constant.

A trapezoidal wing with constant twist is analyzed here. Future studies will investigate the influence of different wing shapes and twist distributions on the system performances. In particular, understanding the optimal lift distribution for a windplane, considering the far wake and the onboard wind turbines, is expected to increase the power production further. The onboard turbines are conceptually designed by modifying their tip speed ratio λt and the parameter Kt. The radial distribution of the parameter k(rt) (see Sect. 2.2) is assumed to be parabolic and a function of Kt as follows:

where Rt is the turbine radius, and Rt0 is the hub radius. Future studies will investigate the effect of different loading shapes (i.e., different distributions of the parameter k(rt)) on the system performances.

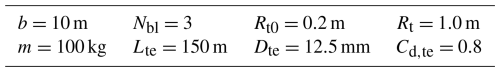

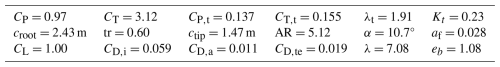

The other fixed parameters are the wing span b, the system mass m, the number of turbine blades Nbl, the tether section drag coefficient Cd,te, the tether diameter Dte, the tether length Lte, and the airfoil polars as a function of the angle of attack (Cl(α),Cd(α)).

By solving this optimization problem, we can get to a design of the wing and of the turbines. To get to the chord and twist of the turbine blades, the Glauert tip correction is applied (Branlard, 2017)4. The turbine design features a constant lift coefficient along the blade span at the design tip speed ratio. In order to achieve a realistic design, the design lift coefficient at the blade tip is lowered to delay stall at lower tip speed ratios, and the chord at the blade root is increased to allow for the hub connection. For these reasons, the chord at the root and at the tip is slightly widened, while the twist is adjusted to keep the same lift force.

Design space exploration

We first explore the optimal design space to study the influence of the turbine position and of the airfoil characteristics on the power output. We chose the parameters in Table 1, which are slightly adjusted with respect to the analyses by Trevisi (2024). The wing is discretized into 100 elements of constant size. The optimization problem (51) is solved in MATLAB with the sequential quadratic programming algorithm implemented in the function fmincon. The solution of the problem takes a few tens of seconds on a standard laptop. Local minima, which are not interesting for this application, can be found when the solver finds solutions with an angle of attack above stall.

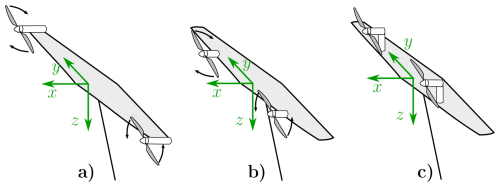

For this study, we compared three turbines' positions (Fig. 6):

- a.

Turbines rotating inboard down, located at one rotor hub radius outward from the wing tip ( m) (indicated with continuous lines in Figs. 7 to 15).

- b.

Turbines rotating inboard down, located in front of the wing ( m) (indicated with dashed lines in Figs. 7 to 15).

- c.

Turbines mounted on pylons (indicated with dotted lines from Figs. 7 to Fig. 15). To model this case, we switch off the interactional aerodynamics between the turbines and the wing while neglecting the parasite drag associated with the pylons. A detailed analysis of the effect of the vertical rotor position on the wing aerodynamics is given by Mehr et al. (2024).

Figure 6Representation of the three windplane layouts considered for the design space exploration study.

Moreover, we consider idealized airfoils on the windplane wing. This is to study the influence of their key metrics on the resulting design. The idealized airfoils have prescribed maximum efficiency at different lift coefficients . The airfoil lift coefficient is modeled to vary linearly with respect to the angle of attack as , and the efficiency Ea is modeled as a parabola , with the peak being equal to Ea,max, achieved at the angle of attack and at the lift coefficient 5.

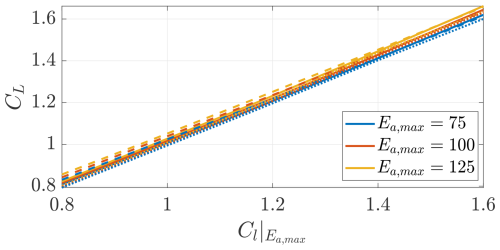

Figure 7 shows the wing lift coefficient CL as a function of the airfoil lift coefficient of maximum efficiency . Recall that the data in the figure represent the solutions of the optimization problem (51). The trends show that it is optimal to design the wing such that it operates the airfoils at their maximum efficiency.

Figure 7Optimal wing lift coefficient as a function of the lift coefficient of maximum airfoil efficiency . Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max and for three turbines' positions (on the pylons (), in front of the wing (), and on the wing tip (−)).

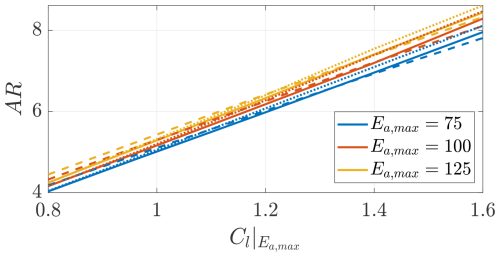

Figure 8 shows the optimal aspect ratio AR as a function of the airfoil lift coefficient of maximum efficiency . The aspect ratio has a similar physical meaning to the solidity of conventional turbines. For increasing , increasing aspect ratios are optimal. The optimal aspect ratio is almost insensible to the airfoil maximum efficiency Ea,max and to the interactional aerodynamics.

The trends in Figs. 7 and 8 are a direct consequence of the optimization objective function, i.e., the power coefficient defined in Eq. (15). This power coefficient informs us about the power for a given wingspan. Similarly, the power coefficient of conventional wind turbines informs us about the power for a given blade span. Conventional wind turbines are designed such that the airfoils along the blade span operate at their maximum efficiency. The chord radial distribution (i.e., the solidity) is settled such that the radial distribution of the induction is optimal, subsequently maximizing the power production (Manwell et al., 2009). Similarly, windplanes optimizing this power coefficient are designed such that the airfoils operate at their maximum efficiency. The chord distribution (i.e., the aspect ratio) is settled such that the induced velocities (or the induced drag) are optimal, subsequently maximizing the power production. Airborne wind energy systems in the literature are designed to maximize the power per a given wing area or, equivalently, the power-harvesting factor ξP (Fasel et al., 2017; Bauer et al., 2018; Echeverri et al., 2020a; Trevisi et al., 2021 among others), which be written as

where the wing area is . Wings designed to maximize ξp have an high aspect ratio and operate at the angle of attack which maximizes the metric , which is achieved, in practice, at the highest lift coefficient. The airfoils are then designed to maximize the metric (Bauer et al., 2018; De Fezza and Barber, 2022; Porta Ko et al., 2023; Rangriz and Kheiri, 2025, among others). The most meaningful objective among the two is the one leading to the lowest levelized cost of energy. The cost of energy of windplanes is expected to increase with the structural material mass, which scales with the cube of the wingspan b3 (Sommerfeld et al., 2022). Therefore, taking the objective as a function of the wingspan (i.e., the power coefficient) is expected to be aligned with a cost-oriented objective. The influence of the two design objectives on the aerodynamic design was first analyzed by Trevisi (2024), and the main conclusions are confirmed here.

Figure 8Optimal wing aspect ratio as a function of the lift coefficient of maximum airfoil efficiency . Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max and for three turbines' positions (on pylons (), in front of the wing (), and on the wing tip (−)).

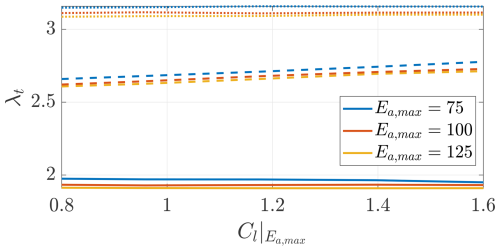

Figures 9 and 10 show the onboard turbine tip speed ratio λt and the turbines' power coefficient CP,t. Recall that the onboard turbines are designed to maximize the windplane power coefficient CP (Eq. 15) and not their own power coefficients CP,t. Considering the interactional aerodynamics, the optimal tip speed ratio decreases to increase the wake swirl and, thus, to increase the change in inflow angle, reducing the induced drag of the wing aerodynamic sections behind the rotors. With the turbines placed at the wing tips, the tip speed ratio is the lowest. Designs with lower tip speed ratios and, thus, lower angular velocities are typically preferable to reduce the noise emission (Chirico et al., 2018).

Figure 9Optimal onboard turbines' tip speed ratios as a function of the lift coefficient of maximum airfoil efficiency . Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max and for three turbines' positions (on pylons (), in front of the wing (), and on the wing tip (−)).

Figure 10Optimal onboard turbine power coefficient as a function of the lift coefficient of maximum airfoil efficiency . Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max and three turbines' positions (on pylons (), in front of the wing (), and on the wing tip (−)).

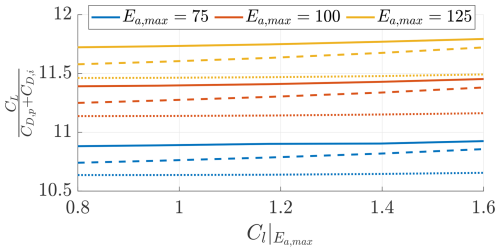

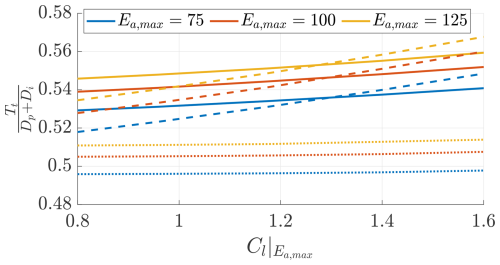

Figure 11 shows the ratio between the lift coefficient and the system drag coefficient. The designs with the turbines at the wing tips achieve the highest because of the turbines effectively reducing the induced drag. Figure 12 shows the ratio between the thrust force Tt and the total wind plane drag Dp+Di. Loyd (1980) shows that, for idealized turbines, the optimal ratio between the turbines' thrust and the total drag is 0.5. The values found in this study confirm this finding, even with a more detailed wind turbine model. For the case with the turbines placed on the pylons, the ratio between the turbines' thrust and drag is slightly lower.

Figure 11Ratio between the wing lift coefficient CL and total drag coefficient . Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max and for three turbines' positions (on pylons (), in front of the wing (), and on the wing tip (−)).

Figure 12Ratio between the onboard turbine thrust force Tt and total drag force Dp+Din. Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max and three turbines' positions (on pylons (), in front of the wing (), and on the wing tip (−)).

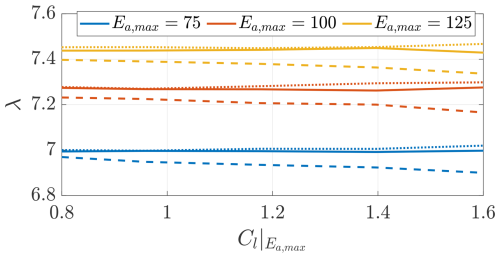

Figure 13 shows the wing speed ratios for the analyzed cases. The windplane flies slightly slower when the turbines are placed in front of the wing. The wing speed ratio is strictly related to the (Fig. 11), but it includes the effect of the turbine thrust and of the far-wake induction (Eq. 13). Recall that the windplane power coefficient CP (Eq. 15) is a function of the onboard turbines' power coefficient CP,t and of the cube of the wing speed ratio λ3.

Figure 13Optimal windplane wing speed ratio as a function of the lift coefficient of maximum airfoil efficiency . Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max and for three turbines' positions (on pylons (), in front of the wing (), and on the wing tip (−)).

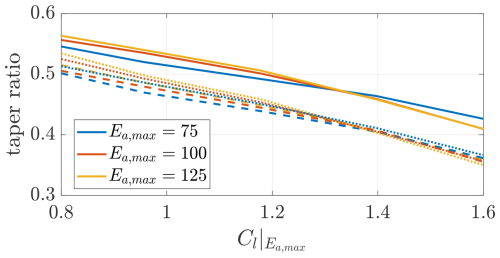

Figure 14 shows the optimal taper ratio as a function of the airfoil lift coefficient of maximum efficiency . Higher taper ratios are preferable if the turbines are placed at the wing tips. This is because higher taper ratio wings have more lifting area behind the turbines, enhancing their beneficial effect on the power production.

Figure 14Optimal taper ratio as a function of the lift coefficient of maximum airfoil efficiency . Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max and three turbines position (on pylons (), in front of the wing (), and on the wing tip (−)).

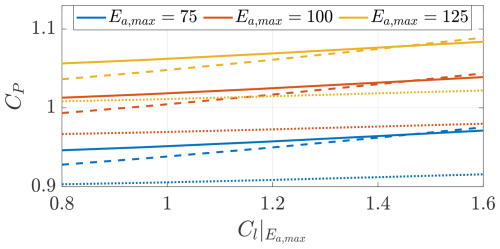

Figure 15 shows the optimal power coefficient CP as a function of the airfoil lift coefficient of maximum efficiency . The power coefficient is sensitive to the maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max and slightly sensitive to . Indeed, larger power coefficients can be achieved with more efficient airfoils. Moreover, the position of the turbines influences the power production. If they are placed on pylons, the power is the lowest even if the parasite drag associated with the pylons is neglected.

Figure 15Optimal power coefficient as a function of the lift coefficient of maximum airfoil efficiency . Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max and three turbines' positions (on pylons (), in front of the wing (), and on the wing tip (−)).

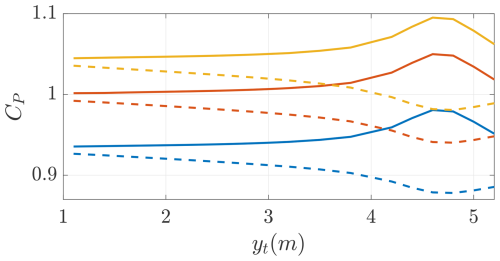

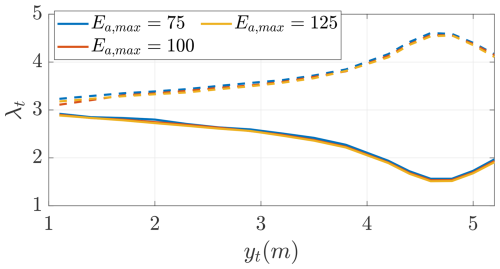

Placing the turbines at the wing tips improves the power production compared to placing them in front of the wing. Note that the turbines rotate inboard down. This can also be seen in Fig. 16, where the position of the turbines yt is moved along the wing for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max with . If the turbines are placed in front of the wing, the wing sections placed inward from the turbine position experience a beneficial change in inflow angle, while the wing sections placed outward experience a disadvantageous change in inflow angle. If the turbines are placed at the wing tips, there are no wing sections outward from the turbine position so that only the beneficial effects in the inward wing sections are experienced. Since the nacelle is not modeled in this study, the portion of wing behind the rotor hub position sees a slight increase in inflow speed. For this reason, the peak in CP corresponds to one rotor hub diameter inward. The peak in real systems will be influenced by the presence of the nacelle and the associated parasite drag, and so the exact position and amplitude of this peak will change consequently. With the turbines getting closer to the wing tip, the interactional aerodynamics become more beneficial for the power production, and, thus, it is optimal for the onboard turbines to increase their wake swirl. For this reason, the optimal onboard turbines' tip speed ratio decreases for the turbines getting closer to the tip, as shown in Fig. 17. To shed light on how big the beneficial interaction is, the figures also show the effect of rotating the turbines in the non-beneficial outboard down direction, where a significant drop in the power coefficient can be observed.

Figure 16Optimal power coefficient as a function of the spanwise position of the turbines for rotation direction inboard down (−) and outboard down (). Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max with .

Figure 17Optimal onboard turbine tip speed ratio as a function of the spanwise position of the turbines for rotation direction inboard down (−) and outboard down (). Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max with .

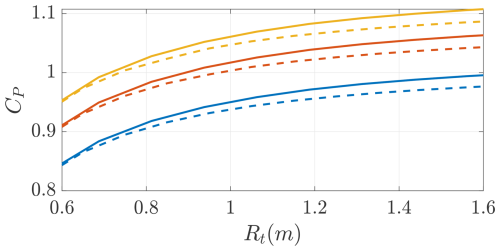

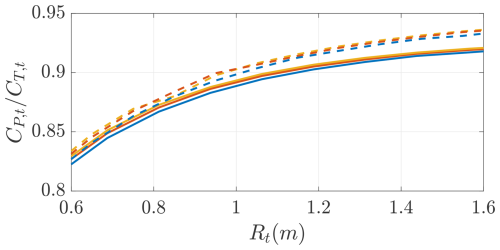

As a final study, the optimal designs are studied as a function of the onboard turbines' radius. Figure 18 shows the optimal power coefficient as a function of the turbines' radius. The power increases for larger radius, such that the turbines can operate at higher (Fig. 19). Higher values indicate that less power is lost in the conversion from thrust power (i.e., the power experienced by the windplane dynamics) to generated power (i.e., the power experienced by the turbines' shaft). When the turbines are placed at the wing tips, a lower is optimal because of the beneficial effects of the interactional aerodynamics. From an aerodynamic point of view, the turbines' radius should be as large as possible. However, the final turbine size will be determined by including structural, electrical, and control considerations. In this study, we keep the turbine radius fixed to Rt=1 m, which seems to be reasonable because the power coefficient is approaching the plateau.

Figure 18Optimal power coefficient as a function of the onboard turbines' radius Rt for two turbines' positions (in front of the wing () and on the wing tip (−)). Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max with .

Figure 19Onboard turbines as a function of the onboard turbines' radius Rt for two turbines' positions (in front of the wing () and on the wing tip (−)). Trends shown for three different values of maximum airfoil efficiency Ea,max with .

To conclude, this study shows that conventional efficient airfoils should be used in the design of windplanes and that the optimal aspect ratio is finite. The windplane should then be designed such that it operates at the lift coefficient corresponding to the airfoil maximum efficiency. The optimal wing taper ratio and the optimal onboard turbines' tip speed ratios are influenced by the interactional aerodynamics. If the turbines are placed at the wing tips and the windplane is designed accordingly, the power can increase considerably (approx 5 %).

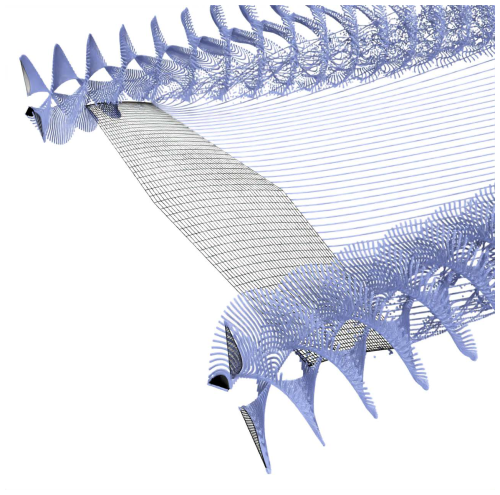

To validate our analytical results, we use DUST6, an open-source aerodynamic simulation software that employs the vortex particle method (Cottet and Koumoutsakos, 2000). This grid-free Lagrangian approach effectively models free wake vorticity evolution and has been developed in accordance with modern FORTRAN standards. It incorporates classical potential-based aerodynamic models, including the lifting-line method (Gallay and Laurendeau, 2015; Piszkin and Levinsky, 1976), surface panels (Piszkin and Levinsky, 1976), and vortex lattice elements (Katz and Plotkin, 2001). While the software assumes incompressible potential flow, compressibility effects are accounted for using the Prandtl–Glauert correction in steady aerodynamic load computations. Additionally, lifting-line and vortex lattice elements incorporate both compressibility and viscous effects through Mach-dependent aerodynamic coefficient tables.

We select the lifting-line element to model the turbine blades because it eliminates the need for explicitly modeling the surface mesh as the flow particles do not interact directly with the blade surface. For the wing, using a lifting-line element can pose challenges in detecting the penetration condition (Niro et al., 2024). Therefore, we opt for the vortex lattice element as it provides accurate results without the higher computational cost associated with surface panel elements.

Figure 20 shows the DUST setup for this simulation. The blue dots represent the vortex particles trailed by the lifting surfaces.

In this section, we present the optimal design and analyze it with DUST. The main inputs for this case study are given in Table 1. The 10 m wingspan windplane was initially designed by Trevisi (2024), and its design is refined here. The NACA4421 airfoils are used for both the wing and the onboard turbines. The chord-based Reynolds number for the wing is above 1×106, while the turbine blades have a chord-based Reynolds number between 200 000 and 500 000. The dependence of the airfoils polars on the Reynolds number can be taken into account in DUST by providing the polars for different Reynolds numbers. This airfoil is chosen because it has a high maximum efficiency (Re=106) at a lift coefficient of , with a relatively large thickness (21 %), which is good for the structural design.

The main optimization results are reported in Table 2. The wing is discretized into 60 elements with a cosine distribution to refine the discretizations after the turbines. The windplane achieves a power coefficient of CP=0.97. The turbines operate with a low tip speed ratio of λt=1.91. Lowering the tip speed ratio increases the wake swirl and thus the inflow angle at the wing sections after the turbines. This low value of λt is also good to limit the acoustic emission (Chirico et al., 2018). The wing has a low aspect ratio of AR=5.1, which is good for structural design and maneuverability, has a taper ratio of tr=0.60 and operates at the maximum efficiency lift coefficient CL=1.00, leading to a wing speed ratio of λ = 7.08. The main drag component is the induced drag, accounting for 66.3 % of the total drag, followed by the tether drag with 21.3 % and by the airfoil drag with 12.4 %. While the breakdown of the drag components is case-dependent, the ratio between the total turbines' thrust and the aerodynamic drag is 56.1 %, similarly to the values in Fig. 12 and to the optimal value of 50 % found by Loyd (1980). The spanwise efficiency eb indicates how efficiently the wing generates lift with respect to the induced drag (Anderson, 2017). It can be estimated as

Modeling the wing with Prandtl lifting-line theory, which is accurate for high aspect ratios, the spanwise efficiency for an isolated wing with an elliptic lift distribution is eb=1. Modeling the wing with the present formulation is accurate even for a low-aspect-ratio wing because the effects of the 2D bound circulation are considered. When accounting for the onboard turbine's influence on the wing, the spanwise efficiency can take values above 1. This value is then representative of the effects of the onboard wind turbines on the wing-induced drag. Note that the spanwise efficiency eb should not be confused with the Oswald efficiency, which also accounts for the parasite drag components of the windplane (Anderson, 2017; Trevisi, 2024) and the induced drag produced by other lifting surfaces on the windplane (e.g., stabilizers).

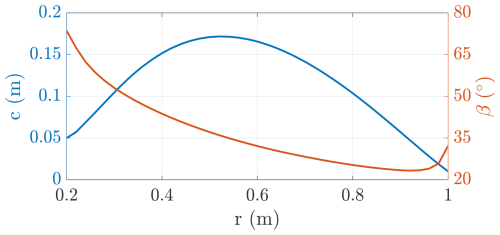

The onboard wind turbines' chord and twist are shown in Fig. 21. The values are given in Table C1. The twist changes drastically from the inner to the outer sections because the operational tip speed ratio λt is very low compared to conventional turbines. Recall that the chord and twist are slightly modified at the root and at the tip to achieve a realistic design with the methodology explained in Sect. 3. This leads to the increase in chord and twist at the root and at the tip.

5.1 Isolated turbine

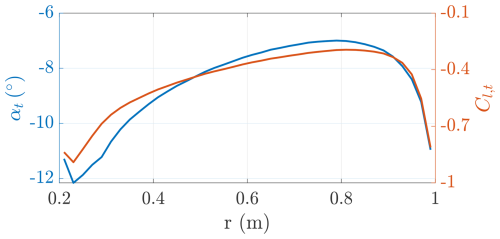

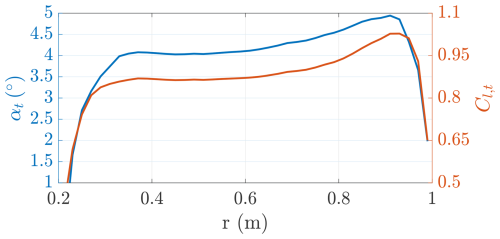

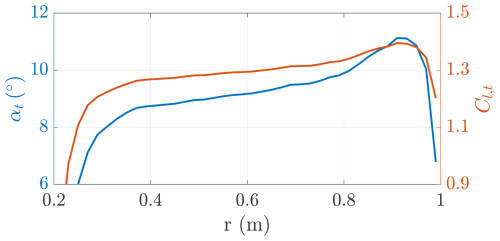

The onboard turbines are now studied with DUST, and the results are compared with the vortex cylinder model. The turbines' blades are modeled as lifting lines with 40 elements, and the simulation is run for eight revolutions with a time step corresponding to 5°, according to the convergence study performed in Appendix B. The turbines are simulated at a tip speed ratio of λt=1.91, finding a thrust coefficient of , a power coefficient of , and an efficiency of . These values are really close to the values found with the vortex cylinder model (Table 2, , , ). The angle of attack and the corresponding sectional lift coefficients along the blade are shown in Fig. 22.

Figure 22Onboard turbines' angle of attack αt and lift coefficient Cl,t as a function of the radial coordinate (λt=1.91).

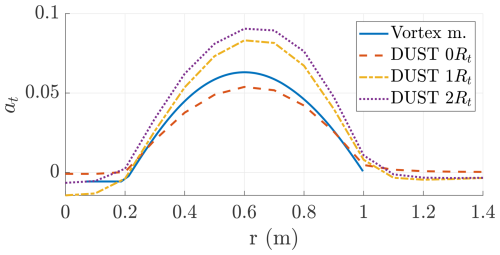

Figure 23 shows the induction of the turbines predicted by the vortex cylinder model and by DUST at a few distances from the rotor plane for λt=1.91. The trends show a good agreement at the rotor plane (0Rt), with DUST predicting slightly lower induced velocities. This could be due to the lower thrust coefficient. The trends after the rotor shows the change in air speed due to the wake expansion.

Figure 23Onboard turbines' induction at as a function of the radial coordinate evaluated with the vortex cylinder model and with DUST at a few downstream distances (λt=1.91).

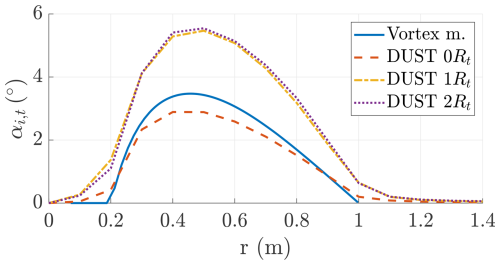

Figure 24 shows the change in inflow angle at different downstream positions. The vortex cylinder model and DUST are in good agreement at the rotor plane, with the vortex cylinder model predicting slightly higher change in inflow angle αi,t.

Figure 24Onboard turbines' induced change in inflow angle αi,t as a function of the radial coordinate evaluated with the vortex cylinder model and with DUST at a few downstream distances (λt=1.91).

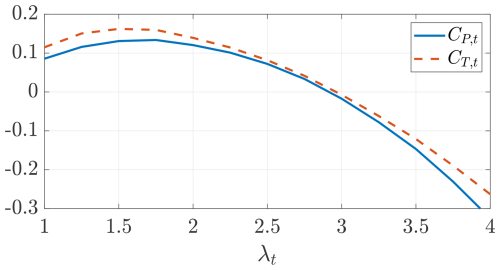

To conclude the analysis of the turbine, the performance is studied for different tip speed ratios λt. Figure 25 shows the power and thrust coefficients of the turbines as a function of their tip speed ratio computed with DUST.

Figure 25Onboard turbines' power coefficient CP,t (−) and thrust coefficient CT,t (− −) as a function of the tip speed ratio λt computed with DUST.

When the thrust coefficient reaches negative numbers, the turbine operates as a propeller. This turbine is designed to be fundamentally different from a conventional one for wind energy conversion. Indeed, its maximum power coefficient is far from the Betz limit as it is designed to maximize the windplane power coefficient CP. The design tip speed ratio of λt=1.91 corresponds approximately to the maximum thrust and power coefficient. This means that these turbines cannot produce higher power and, thus, higher braking force, than their design value. Alborghetti et al. (2025) show how to control the windplane turbines in order to smooth the power output, highlighting the need to almost double the power coefficient with respect to the average value in some parts of the loop. Future works should then modify this design to cope with control requirements.

Figures 26 and 27 show the angle of attack and the lift coefficient along the blades for a tip speed ratio of λt=1.5 and λt=4, respectively. For low λt, the outer aerodynamic sections start experiencing positive stall, with the angle of attack exceeding 10°. For higher λt, the lift coefficients get to negative values, meaning that the thrust is generated in the opposite direction. The aerodynamic sections along the blade get closer to negative stall, which appears at (Re=200 000) or (Re=1 000 000) for the considered airfoil (NACA 4421).

Figure 26Onboard turbines' angle of attack αt and lift coefficient Cl,t as a function of the radial coordinate (λt=1.5).

5.2 Isolated wing

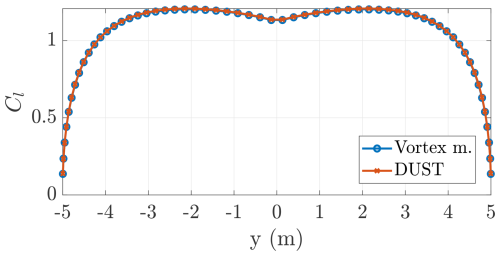

The isolated wing is studied here with DUST and with the Weissinger lifting-line model developed for the design. We model the wing in DUST with vortex lattice elements. This modeling approach does not allow for an explicit evaluation of the wing sections' angle of attack and lift and drag coefficients, which can be recovered from the sectional loads. Moreover, this method only captures the induced drag and not the profile drag. The wing is discretized into 40 elements chord-wise and 60 elements span-wise in DUST, with a cosine distribution to better resolve the aerodynamics close to the wing tips, as shown in Fig. 20. The lifting line has the same span-wise discretization.

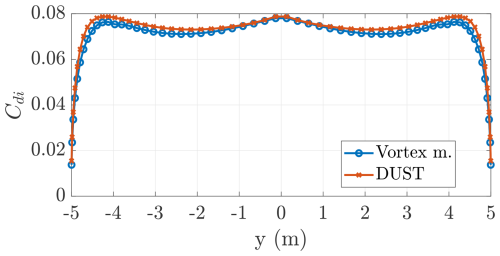

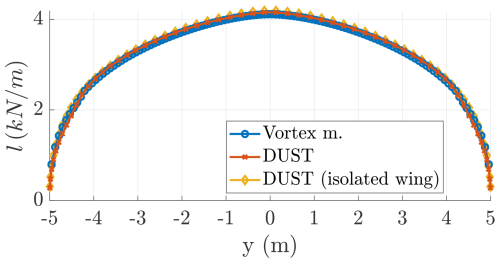

The lift and induced drag coefficients are presented in Figs. 28 and 29, showing a very good matching between the two approaches, while the lift and induced drag are shown in Figs. 30 and 31. The DUST simulation is run with a wing angle of attack of 11°, and the lifting line is run with a wing angle of attack of 12.2° to match the same wing lift coefficient of CL=1.11. The wing-induced drag coefficient estimated with the two methods is (DUST) and (LL). The lift coefficient distribution (Fig. 28) informs us about the angle of attack distribution, which is influenced itself by the induced velocity distribution (recall that a constant twist is considered). The induced velocities for the considered wing are not constant, but they increase towards the tip, leading to lower angles of attack and thus lower lift coefficients.

Figure 28Distribution of lift coefficients along the wing span computed with the vortex model (lifting line) and with DUST.

5.3 Interactional aerodynamics

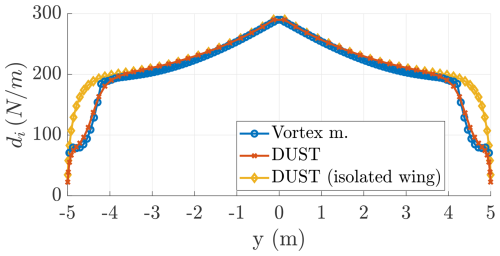

In this section, the interactional aerodynamics between the wind turbines, rotating inboard down, and the wing are studied. The complete problem is analyzed with DUST and with the interactional vortex model proposed in this paper. Figures 30 and 31 show the loads perpendicular to the inflow (lifting forces) and parallel to the inflow (induced drag forces) as estimated with the two methods. The trends of DUST are averaged over the last rotor revolution. The isolated wing results are also shown for reference.

The DUST simulation is run with a wing angle of attack of 11° at va=50 m s−1, and the tip turbines are mounted with a tilt angle of −11°, such that the inflow is perpendicular to the rotor disk. The simulation is run for eight rotor revolutions with a time step equivalent to a rotor angle of 5°.

The vortex model is run with a wing angle of attack of 12.5° at va=50 m s−1 to match the same integral lifting force computed with DUST of L=32.86 kN. The lift distribution of the solution with and without the turbines is almost identical. This is because of the 2-fold effect that the turbines produce on the following wing sections: they reduce the dynamic pressure by slowing down the apparent wind speed, thus reducing lift, and they modify the inflow angle such that the angles of attack increase, thus increasing lift. These two conflicting effects balance out to give a similar lift distribution. The wing-induced drag computed with DUST is Di=2121 N, while, with the vortex model, it is Di=2072 N. The wing spanwise efficiency computed with DUST (Eq. 54) is eb=1.058, similar to the value computed with the vortex model eb=1.080. The wind turbines in DUST have a thrust coefficient of and a power coefficient of , while, in the vortex model, they have the values shown in Table 2 (,).

The very good match between the vortex model and the DUST simulations proves that the vortex model developed in Sect. 2 captures the main physics of the interactional aerodynamics and thus is suitable for design and analysis.

Figure 30Aerodynamic loads acting on the wing perpendicular to the inflow – lifting forces – estimated with the vortex model and with DUST.

5.4 Off-design analysis

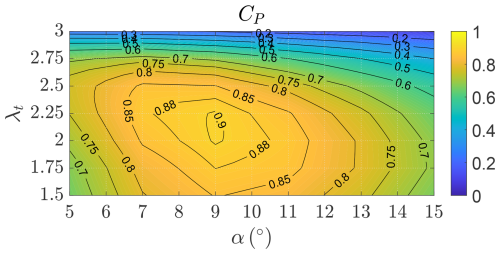

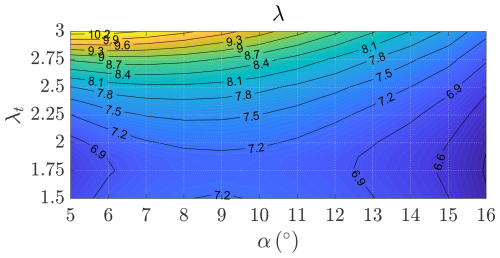

To conclude, we analyze the windplane away from the design point. In this study, the isolated wing aerodynamics are exclusively influenced by the wing angle of attack α, while the isolated turbine aerodynamics are exclusively influenced by the onboard turbines' tip speed ratio λt. Figure 32 shows the windplane power coefficient CP (Eq. 15) as a function of α and λt and is produced with the isolated wing polars (computed with DUST) and the isolated turbines' curves (computed with DUST), thus neglecting the aerodynamic interaction between the turbines and wing. The far-wake induction is computed by estimating the tip vortices' strength Γ0 (Eq. 45) and their position yv (Eq. 46) from the local lift distribution in DUST.

Figure 32Power coefficient CP as a function of the wing angle of attack α and the turbines' tip speed ratio λt, neglecting the aerodynamic interaction between the turbines and wing.

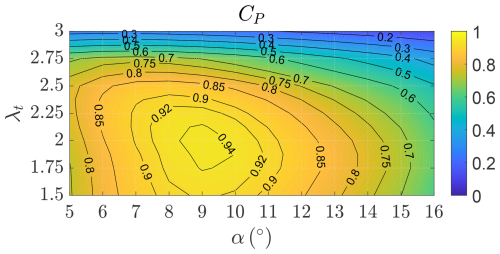

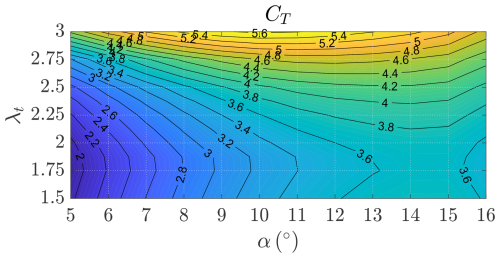

To include the interactional aerodynamics, we run DUST simulations for different combinations of α and λt, and we evaluate the windplane performances. Figure 33 shows the windplane power coefficient CP (Eq. 15). The interactional aerodynamics are responsible for an increase in power production from CP=0.90 to CP=0.94. The power coefficient has an unconstrained maximum at α=9° and λt=2, which are far from the stall regions of the wing and of the turbine blades. While the power coefficient CP informs us about the power production of the windplane, the thrust coefficient CT, as in Fig. 34 (Eq. 16), informs us about the aerodynamic force generated by the windplane. To conclude the analyses of the design, Fig. 35 shows the wing speed ratio, informing us about the windplane speed u, as a function of α and λt. Clearly, the turbines have the strongest influence on the wing speed ratio as they act as a brake. It can be also noted that, for a given λt, λ has a maximum.

These three figures (Figs. 33 to 35) can be used to plan the high-level control of the windplane. Indeed, the windplane should be operated at the maximum power coefficient to maximize power production before the rated wind speed. To reduce the aerodynamic power after the rated wind speed, one could decrease the power coefficient by modifying the angle of attack α and the turbines' tip speed ratio λt. The control system might be developed to look for the combination of α and λt which minimizes the loads while keeping the desired CP. By inspecting Fig. 34, the more sensible strategy to reduce the CT is to reduce the angle of attack α. Increasing the tip speed ratio λt does decrease power but also increases the wing speed ratio λ (Fig. 35) and thus loads (Fig. 34).

Figure 33Power coefficient CP as a function of the wing angle of attack α and the turbine tip speed ratio λt evaluated with DUST.

Figure 34Thrust coefficient CT as a function of the wing angle of attack α and the turbine tip speed ratio λt evaluated with DUST.

Figure 35Wing speed ratio λ as a function of the wing angle of attack α and the turbine tip speed ratio λt evaluated with DUST.

Finally, Fig. 36 shows the induced drag as a function of the onboard turbines' tip speed ratio for α=10°. For low λt, the turbines swirl contributes largely to the reduction in the induced drag.

In this paper, we develop a new methodology for the aerodynamic design and analysis of windplanes (the aircraft of fly-gen airborne wind energy systems), and we verify the methodology by comparison with higher-fidelity models and characterize the windplane design further with the vortex particle method.

In the method, a novel engineering model for the onboard turbines' aerodynamics, the wing aerodynamics, and their interactional aerodynamics is employed and coupled to a windplane steady-state model and a windplane far-wake model. The turbines are modeled as vortex cylinders, while the wing is modeled with a lifting-line formulation that accounts for the turbines' induced velocities. An optimization problem is formulated to concurrently design the turbines and the wing, assuming a trapezoidal planform and constant twist. The optimization objective is the windplane power coefficient, which uses as the reference area a disk with a radius equal to the wingspan. This is equivalent to taking as the objective the power while keeping the wingspan fixed. Other metrics could also be used as objectives in this framework.

Using the proposed approach, a design space exploration study is carried out to investigate the influence of turbine position and airfoil characteristics on the optimal design. We find that placing the turbines at the wing tips and rotating them inboard down leads to higher power production compared to mounting them on pylons (i.e., no interactional aerodynamics) or placing them in front of the wing. The key interactional effect arises from the turbine wake swirl, which modifies the inflow angle on the downstream wing sections. By choosing the correct rotor direction, inboard down, and placing the turbines at the wing tips, the outer part of the wing experiences an increase in inflow angles and thus an increase in performance. To enhance this beneficial effect, the optimal designs feature a larger wing taper ratio and a lower turbine tip speed ratio compared to other configurations. The design space exploration study also reveals that conventional efficient airfoils (high ) should be used in the design of windplanes, confirming the results of Trevisi (2024), rather than airfoils optimized for the metric commonly used in the literature. The wing aspect ratio is then designed such that the power is maximized when the wing, with constant twist, operates at the lift coefficient correspondent to the airfoil maximum efficiency.

Later, NACA4421 airfoils are considered for the aerodynamic optimization of the wing and of the turbines, placed at the wing tips. The turbines are characterized by an optimal tip speed ratio of λt=1.91, which dictates their twist and chord distribution. The wing is designed with a low aspect ratio (AR=5.1) and to operate at the lift coefficient corresponding to the airfoil maximum efficiency. The vortex models of the isolated turbines and the isolated wing and their aerodynamic interaction show very good agreement with the solution of the lifting line, the vortex lattice method, and the vortex particle method implemented in open-source code DUST. The behavior of the turbines is also studied with DUST as a function of the tip speed ratio. Finally, the windplane is studied with DUST at different angles of attack α and at different turbine tip speed ratios λt, finding the maximum power coefficient CP=0.94 at α=9° and λt=2. The optimal operating point is far from the stall regions of the wing and of the turbine blades.

This paper describes a new comprehensive theory of the windplane aerodynamics, allowing for an in-depth understanding of the main aerodynamic phenomena. This work will be used as a baseline for more detailed aerodynamic studies on the turbines, wing, and tail. It could also be used for computing the aerodynamic derivatives to be used in flight stability analyses, for the closed-loop control development, for the structural design, and for airborne wind farm studies.

| Latin symbols | |

| A | Wing area |

| af | Induction due the far wake |

| ar | Normalized axial velocity of the far- |

| wake vortex rings | |

| AR | Wing aspect ratio |

| at | Induction of the onboard turbine |

| b | Wing span |

| CD | System drag coefficient |

| CD,i | Induced drag coefficient |

| Cd,i | Sectional induced drag coefficient |

| CD,a | Wing drag coefficient due to the airfoils |

| CD,te | Equivalent tether drag coefficient |

| Cd,te | Drag coefficient of the tether section |

| CL | Wing lift coefficient |

| CP | Windplane power coefficient |

| CP,t | Onboard wind turbine power coefficient |

| CT | Windplane thrust coefficient |

| CT,t | Onboard wind turbine thrust coefficient |

| Dte | Tether diameter |

| E | Windplane aerodynamic efficiency, |

| including the tether and the turbine thrust | |

| eb | Spanwise efficiency |

| Lte | Tether length |

| m | Windplane mass plus one-third of the |

| tether mass | |

| R0 | Turning radius |

| Rt | Onboard turbine radius |

| Rt0 | Onboard turbine hub radius |

| tr | Taper ratio |

| u | Windplane tangential velocity |

| va | Apparent wind speed in the near wake |

| vw | Wind speed |

| Greek symbols | |

| α | Wing angle of attack, defined as the angle |

| between the x direction and the | |

| apparent wind speed va | |

| αi,t | Induced change in inflow angle |

| at the wing due to the turbine swirl | |

| γn | Inflow angle in the near wake |

| λ | : wing speed ratio |

| λt | : onboard turbine tip speed ratio |

| Φ | Opening angle of the cone swept by the |

| tether during one loop | |

| ρ | Air density |

| ξt | normalized onboard |

| turbines radius |

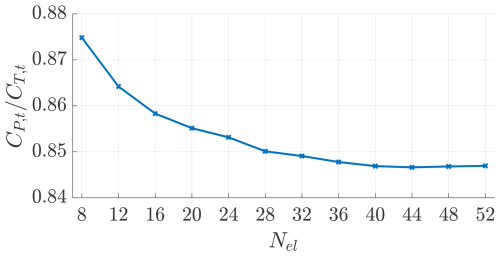

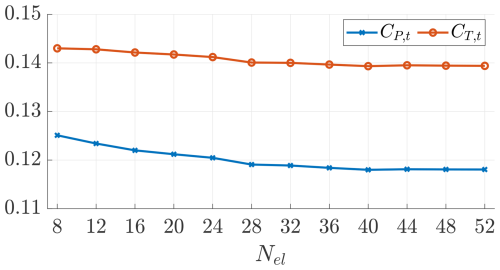

To select the number of lifting-line elements for the turbines for the simulations in DUST, we conduct a convergence study on an earlier turbine design, similar to the final design. For the turbines, we set a number of elements Nel and gradually increased them until the results converged, as shown in Figs. B1 and B2, leading to the use of 40 elements for the blade lifting line (Niro et al., 2024).

Figure B1Power coefficient CP,t and thrust coefficient CT,t as a function of the lifting-line number of elements.

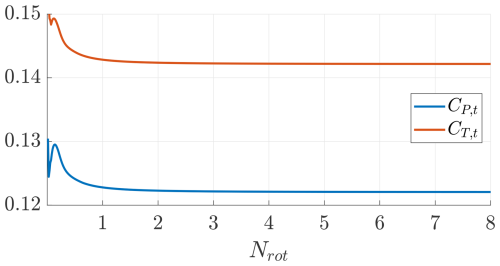

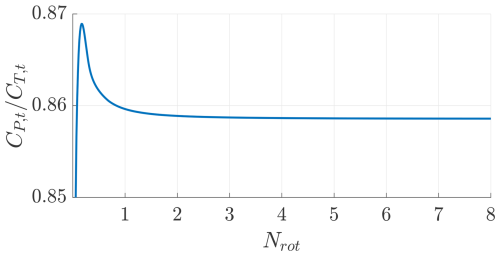

Figures B3 and B4 show the power and thrust coefficients and their ratio as a function of the number of rotor rotations. Even if a good convergence is experienced after approximately three rotations, the simulations in this paper are run for eight rotor revolutions. This second convergence study was carried out on the final turbine design.

DUST is open source and available online at https://www.dust.polimi.it/ (last access: 4 December 2025). The input files, and the code developed to pre-process the simulations and post-process the results are produced by us and are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18200345 (Trevisi, 2026).

The DUST simulation results are produced by us and are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18200345 (Trevisi, 2026). The other data underlying our research are available in the manuscript.

FT conceptualized and developed the research methods, produced the results, and wrote the draft version of the paper. MG contributed to the conceptualization of the paper and to the development of the aerodynamic model and revised the paper. GC contributed to the conceptualization of the paper and to setting up the DUST simulations and revised the paper. LF contributed to the conceptualization of the paper and to the optimal problem formulation and revised the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, pub- lished maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This research has been supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Research with the project “DeepAirborne – Advanced Modeling, Control and Design Optimization Methods for Deep Offshore Airborne Wind Energy” (NextGenerationEU fund, grant no. P2022927H7); by the Italian Ministry of University and Research with the PNRR M4C2 project “NEST – Network 4 Energy Sustainable Transition” (NextGenerationEU fund, grant no. PE00000021-D43C2200309000); by the MERIDIONAL project, which receives funding from the European Union's Horizon Europe Programme (grant agreement no. 101084216); and by the Danish EUDP, Energy Technology Development and Demonstration Programme, with the project “IEA Wind Task: Airborne Wind Energy” (grant no. J.134-21007).

This paper was edited by Roland Schmehl and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Alborghetti, M., Trevisi, F., Boffadossi, R., and Fagiano, L.: Optimal Power Smoothing of Airborne Wind Energy Systems via Pseudo-Spectral Methods and Multi-objective Analysis, in: 2025 European Control Conference (ECC), 2446–2451, https://doi.org/10.23919/ECC65951.2025.11187024, 2025. a

Anderson, J.: Fundamentals of Aerodynamics, McGraw-Hill Education, sixth edn., ISBN 9781259251344, 2017. a, b

Bauer, F., Kennel, R. M., Hackl, C. M., Campagnolo, F., Patt, M., and Schmehl, R.: Drag power kite with very high lift coefficient, Renewable Energy, 118, 290–305, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2017.10.073, 2018. a, b, c, d, e

Branlard, E.: Wind Turbine Aerodynamics and Vorticity-Based Methods, Springer Cham, ISBN 978-3-319-55163-0, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55164-7, 2017. a

Branlard, E. and Gaunaa, M.: Cylindrical vortex wake model: right cylinder, Wind Energy, 18, 1973–1987, https://doi.org/10.1002/we.1800, 2015. a

Branlard, E. and Gaunaa, M.: Superposition of vortex cylinders for steady and unsteady simulation of rotors of finite tip-speed ratio, Wind Energy, 19, 1307–1323, https://doi.org/10.1002/we.1899, 2016. a

Chirico, G., Barakos, G. N., and Bown, N.: Numerical aeroacoustic analysis of propeller designs, The Aeronautical Journal, 122, 283–315, https://doi.org/10.1017/aer.2017.123, 2018. a, b

Cottet, G.-H. and Koumoutsakos, P.: Vortex methods – theory and practice, ISBN 978-0-521-62186-1, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511526442, 2000. a

Damiani, R., Wendt, F. F., Jonkman, J. M., and Sicard, J.: A Vortex Step Method for Nonlinear Airfoil Polar Data as Implemented in KiteAeroDyn, in: AIAA Scitech 2019 Forum, https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2019-0804, 2019. a, b

De Fezza, G. and Barber, S.: Parameter analysis of a multi-element airfoil for application to airborne wind energy, Wind Energ. Sci., 7, 1627–1640, https://doi.org/10.5194/wes-7-1627-2022, 2022. a, b

Diehl, M.: Airborne Wind Energy: Basic Concepts and Physical Foundations, in: Airborne Wind Energy, edited by: Ahrens, U., Diehl, M., and Schmehl, R., 3–22, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, ISBN 978-3-642-39965-7, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39965-7_1, 2013. a

Echeverri, P., Fricke, T., Homsy, G., and Tucker, N.: The Energy Kite. Selected Results From the Design, Development and Testing of Makani's Airborne Wind Turbines. Part I., Tech. rep., Makani Technologies LLC, https://x.company/projects/makani/ (last access: 4 December 2025), 2020a. a, b, c

Echeverri, P., Fricke, T., Homsy, G., and Tucker, N.: The Energy Kite. Selected Results From the Design, Development and Testing of Makani's Airborne Wind Turbines. Part II., Tech. rep., Makani Technologies LLC, https://x.company/projects/makani/ (last access: 4 December 2025), 2020b. a

Fagiano, L. and Schnez, S.: On the take-off of airborne wind energy systems based on rigid wings, Renewable Energy, 107, 473–488, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2017.02.023, 2017. a

Fagiano, L., Quack, M., Bauer, F., Carnel, L., and Oland, E.: Autonomous Airborne Wind Energy Systems: Accomplishments and Challenges, Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems, 5, 603–631, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-control-042820-124658, 2022. a

Fasel, U., Keidel, D., Molinari, G., and Ermanni, P.: Aerostructural optimization of a morphing wing for airborne wind energy applications, Smart Materials and Structures, 26, 095043, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665X/aa7c87, 2017. a, b

Frirdich, A.: Rotor Design Procedure for a Drag Power Kite, Master's thesis, Technische Universität München, https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/60a7e7bc31a1214a325709bc/6446c7aadf11605410de910f_MT_Frirdich.pdf (last access: 4 December 2025), 2019. a

Gallay, S. and Laurendeau, E.: Nonlinear Generalized Lifting-Line Coupling Algorithms for Pre/Poststall Flows, AIAA Journal, 53, 1784–1792, https://doi.org/10.2514/1.J053530, 2015. a

Gaunaa, M., Forsting, A. M., and Trevisi, F.: An engineering model for the induction of crosswind kite power systems, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1618, 032010, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1618/3/032010, 2020. a

Katz, J. and Plotkin, A.: Low-Speed Aerodynamics, Cambridge Aerospace Series, Cambridge University Press, 2 edn., https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511810329, 2001. a

Kitekraft GmbH: Building Flying Wind Turbines, https://www.kitekraft.de/ (last access: 18 June 2025), 2025. a

Li, A., Gaunaa, M., Pirrung, G. R., Meyer Forsting, A., and Horcas, S. G.: How should the lift and drag forces be calculated from 2-D airfoil data for dihedral or coned wind turbine blades?, Wind Energ. Sci., 7, 1341–1365, https://doi.org/10.5194/wes-7-1341-2022, 2022. a

Loyd, M.: Crossswind Kite Power, Journal of Energy, 4, 106–111, 1980. a, b, c

Makani Technologies LLC: Makani. Harnessing wind energy with kites to create renewable electricity, https://x.company/projects/makani/ (last access: 18 June, 2025), 2025. a

Manwell, J. F., McGowan, J. G., and Rogers, A. L.: Wind Energy Explained: Theory, Design and Application, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, ISBN 9781119994367, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119994367, 2009. a

Mehr, J., Alvarez, E. J., and Ning, A.: Interactional Aerodynamics Analysis of a Multirotor Energy Kite, Wind Energy, e2957, https://doi.org/10.1002/we.2957, 2024. a, b

Miranda, L. and Brennan, J.: Aerodynamic effects of wingtip-mounted propellers and turbines, 4th Applied Aerodynamics Conference, https://doi.org/10.2514/6.1986-1802, 1986. a, b

Niro, C., Savino, A., Cocco, A., and Zanotti, A.: Mid-fidelity numerical approach for the investigation of wing-propeller aerodynamic interaction, Aerospace Science and Technology, 146, 108950, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2024.108950, 2024. a, b, c

Patterson, J. J. and Bartlett, G.: Effect of a wing-tip mounted pusher turboprop on the aerodynamic characteristics of a semi-span wing, AIAA, https://doi.org/10.2514/6.1985-1286, 1985. a

Piszkin, S. and Levinsky, E. S.: Nonlinear Lifting Line Theory for Predicting Stalling Instabilities on Wings of Moderate Aspect Ratio, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:107820302 (last access: 4 December 2025), 1976. a, b

Porta Ko, A., Smidt, S., Schmehl, R., and Mandru, M.: Optimisation of a Multi-Element Airfoil for a Fixed-Wing Airborne Wind Energy System, Energies, 16, https://doi.org/10.3390/en16083521, 2023. a, b

Prandtl, L.: Induced drag of multiplanes, Tech. rep., NACA-TN-182, https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19930080964 (last access 4 December 2025), 1924. a

Rangriz, S. and Kheiri, M.: Design of Optimal Airfoils for Crosswind Kite Power Systems, AIAA Journal, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.2514/1.J065382, 2025. a, b

Sinnige, T., Stokkermans, T., van Arnhem, N., and Veldhuis, L. L.: Aerodynamic Performance of a Wingtip-Mounted Tractor Propeller Configuration in Windmilling and Energy-Harvesting Conditions, AIAA, https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2019-3033, 2019a. a

Sinnige, T., van Arnhem, N., Stokkermans, T. C. A., Eitelberg, G., and Veldhuis, L. L. M.: Wingtip-Mounted Propellers: Aerodynamic Analysis of Interaction Effects and Comparison with Conventional Layout, Journal of Aircraft, 56, 295–312, https://doi.org/10.2514/1.C034978, 2019b. a

Snyder, M. H. and Zumwalt, G. W.: Effects of wingtip-mounted propellers on wing lift and induced drag, Journal of Aircraft, 6, 392–397, https://doi.org/10.2514/3.44076, 1969. a

Sommerfeld, M., Dörenkämper, M., De Schutter, J., and Crawford, C.: Scaling effects of fixed-wing ground-generation airborne wind energy systems, Wind Energ. Sci., 7, 1847–1868, https://doi.org/10.5194/wes-7-1847-2022, 2022. a

Trevisi, F.: Conceptual design of windplanes, Phd thesis, Politecnico di Milano, https://hdl.handle.net/10589/216694, 2024. a, b, c, d, e, f, g

Trevisi, F.: Code and data for the final publication of “Concurrent aerodynamic design of the wing and the turbines of AWESs” (Version v0), Zenodo [code, data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18200346, 2026. a, b

Trevisi, F., Gaunaa, M., and Mcwilliam, M.: The Influence of Tether Sag on Airborne Wind Energy Generation, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1618, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1618/3/032006, 2020. a, b

Trevisi, F., Gaunaa, M., and Mcwilliam, M.: Configuration optimization and global sensitivity analysis of Ground-Gen and Fly-Gen Airborne Wind Energy Systems, Renewable Energy, 178, 385–402, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.06.011, 2021. a, b

Trevisi, F., Riboldi, C. E. D., and Croce, A.: Refining the airborne wind energy system power equations with a vortex wake model, Wind Energ. Sci., 8, 1639–1650, https://doi.org/10.5194/wes-8-1639-2023, 2023a. a, b

Trevisi, F., Riboldi, C. E. D., and Croce, A.: Vortex model of the aerodynamic wake of airborne wind energy systems, Wind Energ. Sci., 8, 999–1016, https://doi.org/10.5194/wes-8-999-2023, 2023b. a, b, c, d, e, f

Trevisi, F., Sabug, L. J., and Fagiano, L.: A Gaussian wake model for Airborne Wind Energy Systems, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 3016, 012038, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/3016/1/012038, 2025. a

Tucker, N.: Airborne Wind Turbine Performance: Key Lessons From More Than a Decade of Flying Kites, in: The Energy Kite Part I., edited by: Echeverri, P., Fricke, T., Homsy, G., and Tucker, N., 93–224, Makani Technologies LLC, https://x.company/projects/makani/# (last access: 4 December 2025), 2020. a

Tugnoli, M., Montagnani, D., Syal, M., Droandi, G., and Zanotti, A.: Mid-fidelity approach to aerodynamic simulations of unconventional VTOL aircraft configurations, Aerospace Science and Technology, 115, 106804, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2021.106804, 2021. a

Vander Lind, D.: Analysis and Flight Test Validation of High Performance AirborneWind Turbines, in: Airborne Wind Energy, edited by: Ahrens, U., Diehl, M., and Schmehl, R., 473–490, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, ISBN 978-3-642-39965-7, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39965-7_28, 2013. a

Veldhuis, L.: Review of propeller-wing aerodynamic interference, ICAS 2004-6.3.1, in: 24th International Congress of the Aeronautical Sciences, Yokohama, Japan, https://www.icas.org/icas_archive/ICAS2004/ABSTRACTS/065.HTM (last access: 4 December 2025), 2004. a

Vermillion, C., Cobb, M., Fagiano, L., Leuthold, R., Diehl, M., Smith, R. S., Wood, T. A., Rapp, S., Schmehl, R., Olinger, D., and Demetriou, M.: Electricity in the air: Insights from two decades of advanced control research and experimental flight testing of airborne wind energy systems, Annual Reviews in Control, 52, 330–357, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcontrol.2021.03.002, 2021. a

Weissinger, J.: The Lift Distribution of Swept-Back Wings, Tech. rep., National Advisory Commitee for Aeronautics, Langley Aeronautical Lab, NACA Technical Memorandum 1120, https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20030064148 (last access: 4 December 2025), 1947. a

WindLift: The Future of Energy is Airborne, https://windlift.com/ (last access: 18 June, 2025), 2025. a

This power-harvesting factor uses the wing planform area as the reference area.

This power coefficient uses a disk with a radius equal to the wingspan as the reference area.

The tangential velocity jumps from zero just in front of the disk to twice the disk value after the disk. The axially induced velocity undergoes a smooth variation from zero far upstream to twice the disk induction in the far wake behind the disk. In the regions close to the disk, the axial inductions depend on the loading of all annular strips.

The angle of attack α is measured in radians. for , for , and for .

https://www.dust.polimi.it/ (last access: 4 December 2025)

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Windplane aerodynamics model

- Windplane aerodynamic design problem

- Vortex particle method: DUST

- Optimal aerodynamic design

- Conclusions

- Appendix A: Nomenclature

- Appendix B: Turbine convergence study